At Optique Opticians in Battersea, we believe most children have excellent sight and do not need to wear glasses.

Some children may have vision screening done at school (between the ages of four and five). This is important because many children will not realise they have a problem – children assume the way they see is normal – they will have never known anything different. However, the earlier any problems are picked up, the better the outcome.

Problems children might have:

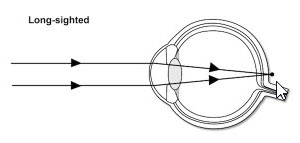

Long-sightedness

If you are long-sighted, your eyes are too short and the light that comes into your eyes is focused behind the retina rather than on it. This means that eyes have to work hard to re-focus, particularly on things that are close up.

This can give you discomfort, headaches or problems with near vision. You may need to wear glasses all the time or just for close work, such as reading, writing or computer use. In older people, as re-focusing becomes more difficult, distance vision may also become blurred.

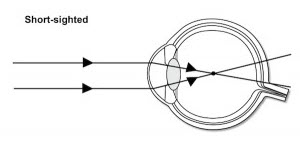

Short-sightedness

The light coming into the eye needs to be focused on the back of the eye (the retina) for you to see clearly. Some people have eyes that are too long, so the light focuses in front of the retina. This means that they cannot see things clearly if they are far away from them (such as the TV) whilst their near vision is usually clear.

Short sight normally develops in childhood or adolescence and is often first noticed at school.

Astigmatism

If your eye is shaped more like a rugby ball than a football, light rays are focused on more than one place in the eye, so you don’t have one clear image. This may make it hard to tell ‘N’ from ‘H’, for instance.

Most people have a small amount of astigmatism, which may not need correcting. However, if your vision is blurred or you get headaches, your optometrist may recommend that you wear glasses all the time – or just for specific tasks.

Glasses which correct this may feel strange at first, although vision with the glasses will be clear.

Lazy Eye

About 2% to 3% of all children have a lazy eye, clinically known as ‘amblyopia’. This may occur because they have one eye that is much more short or long-sighted than the other, or they may have a squint (where the eyes are not lined up together).

If a lazy eye is not treated before the child is aged seven or eight, the child’s vision may be permanently affected.

Children with learning difficulties are more likely to have problems with their vision,

The treatment will depend on what is causing the lazy eye:

- If it is simply because the child needs glasses, the optometrist will prescribe these to correct sight problems

- If the child has a squint, this may be fully or partially corrected with glasses. However, some children may need an operation, which can take place as early as a few months of age

- If the child has a lazy eye, eye drops or patching the good eye can help to encourage them to use the lazy eye to make it see better.

Some children find it hard to get on with patching or with glasses although they will improve their vision.

Squint

Squint (also known as strabismus) is a condition that arises because of an incorrect balance of the muscles that move the eye, faulty nerve signals to the eye muscles and focusing faults (usually long sight). If these are out of balance, the eye may turn in (converge), turn out (diverge) or sometimes turn up or down, preventing the eyes from working properly together.

Squint can occur at any age. A baby can be born with a squint or develop one soon after birth. If a child appears to have a squint at any age from six weeks onwards, it is important to seek professional advice quickly. Many children with squints have poor vision in the affected eye. If treatment is needed, the sooner it is started the better the results.

Causes of Squint

There are several types of squint. The cause is not always known, but some children are more likely to develop it than others. Among the possible causes are:

Congenital squint

Sometimes a baby is born with a squint, although it may not be obvious for a few weeks. In about half of such cases, there is a family history of squint or the need for glasses. The eye muscles are usually at fault. If squint is suspected, it is important that the baby be referred for accurate assessment at the earliest opportunity. Sometimes a baby has what is known as ‘pseudo squint’ which is related to the shape of the face, but a baby with a true squint will not grow out of it.

Long sight (hypermetropia)

Long sightedness can sometimes lead to a squint developing as the eyes ‘over-focus’ in order to see clearly. In an attempt to avoid double vision, the brain may automatically respond by ‘switching off’ the image from one eye and turning the eye to avoid using it.

If left untreated, a ‘lazy eye’ (amblyopia) may result. The most common age for this type of squint to start is between 10 months and two years, but it can occur up to the age of five years. It is usually first noticed when a baby is looking at a toy, or at a later age when a child is concentrating on close work, such as a jigsaw or reading.

Childhood illnesses

Squint may develop following an illness such as measles or chickenpox. This may mean that a tendency to squint has been present but, prior to the illness, the child was able to keep his or her eye straight.

Nerve damage

In some cases a difficult delivery of a baby or illness damaging a nerve can lead to a squint.

Symptoms of Squint

How can I tell if my child has a squint?

People often think that they can tell if a child has a squint if the eyes look unusual or the two eyes look different. This is not necessarily a squint. Squints are often difficult to detect, especially in younger children. Older children may complain of eyesight problems such as double vision. If it is suspected that a child has a squint, your health visitor, child health clinic, GP or school doctor/nurse should be asked about a referral to an optometrist, ophthalmic medical practitioner or hospital eye clinic for assessment.

Treatment for Squint

Certainly the appearance can lead to problems for the child, but a squint is not merely a cosmetic problem. If left untreated, it can lead to a permanent visual defect in the squinting eye. It is never too late to treat a squint which is cosmetically desirable and glasses or surgery can give good results in many cases.

What can be done?

Treating a squint varies accordingly to the type of squint. An operation is not always needed. The main forms of treatment are:

- Glasses – to correct any sight problems, especially long sight.

- Occlusion – patching the good eye to encourage the weaker eye to be used. This is usually done under the supervision of an orthoptist.

- Surgery – this is used with congenital squints, together with other forms of treatment in older children, if needed. Surgery can be performed as early as a few months of age.

Colour Blindness

People with colour vision deficiency are unable to see some colours clearly and accurately.

They may find it difficult to distinguish between different colours. For example, reds, oranges, yellows, browns and greens may all appear to be a similar colour to someone with a red-green deficiency. Other types of colour vision deficiency may make it difficult to identify pale or deep colours, particularly if the light is poor. In many cases, completely different colours may appear to be the same – for example, people often confuse red with black.

Colour vision deficiency can vary in severity. Some people are unaware they have a colour deficiency until they have a colour vision test.

Read more about the symptoms of colour vision deficiency.

What causes colour vision deficiency?

In most cases, colour vision deficiency is an inherited condition which can be passed down by your parents

In the normal eye the retina is made up of three different types of cones. Some cones are best at capturing long wavelength (red) light. Others catch medium wavelength (green) light, while other cones respond best to short wavelength (blue) light. The signals from these cones are sent to the brain where they are perceived as colour.

If you have a colour vision deficiency, one or more cones will be missing, which means you'll be unable to see the full spectrum of colours.

Types of colour vision deficiency

The three main types of colour vision deficiency are:

- red-green colour deficiencies (two separate conditions)

- blue-yellow colour deficiency (one condition).

- Red-green colour deficiencies

Red-green colour deficiencies are the most common types affecting significantly more men than women (1 in 12 men have red-green colour vision deficiencies, but only 1 in 200 women).

Blue-yellow colour deficiency

Blue-yellow colour deficiency is very rare, and usually associated with a deficit in the S-cones. People with this type of colour deficiency have difficulty distinguishing between shades of blue and green. Blue-yellow colour deficiency occurs equally in men and women.

Recognising colour vision deficiency

Many people first become aware they have a colour vision deficiency when they have a problem identifying colours correctly. For example, a child may have difficulty naming colours or may struggle to read a coloured map or document.

It's important to identify a colour vision problem early. Your child's learning experience can be adapted if they are diagnosed at an early age and their teachers are made aware that they have the deficiency.

Colour vision testing isn't usually part of a standard NHS eye test, so some people with a colour vision deficiency may not realise they have it.

Treating colour vision deficiency

There's currently no cure for inherited colour vision deficiency as it not possible replace the cone cells in the retina. There are no long term health problems and those affected can lead a normal healthy life. These colour vision deficiencies can be detected and graded using various colour vision tests.

Specialist spectacle lenses are available to help with colour Deficiency .

For help and advice on Children's Eyecare, visit Optique Opticians in Battersea, 276 Battersea Park Road, Battersea, London, SW11 3BS. Tel: 020 72282754

The information on this site is for Educational Purposes Only and is not designed to diagnose, treat, prevent or cure any health conditions.